Born again Christains Are Likely to Hold Conservative Views

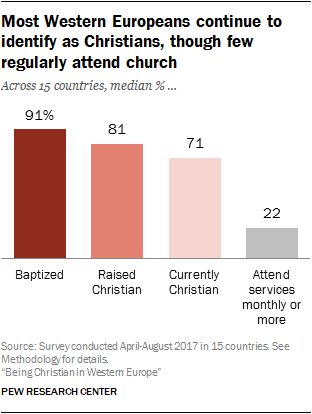

Western Europe, where Protestant Christianity originated and Catholicism has been based for nearly of its history, has become ane of the world's most secular regions. Although the vast majority of adults say they were baptized, today many do not describe themselves as Christians. Some say they gradually drifted abroad from religion, stopped believing in religious teachings, or were alienated past scandals or church positions on social problems, co-ordinate to a major new Pew Research Center survey of religious beliefs and practices in Western Europe.

Western Europe, where Protestant Christianity originated and Catholicism has been based for nearly of its history, has become ane of the world's most secular regions. Although the vast majority of adults say they were baptized, today many do not describe themselves as Christians. Some say they gradually drifted abroad from religion, stopped believing in religious teachings, or were alienated past scandals or church positions on social problems, co-ordinate to a major new Pew Research Center survey of religious beliefs and practices in Western Europe.

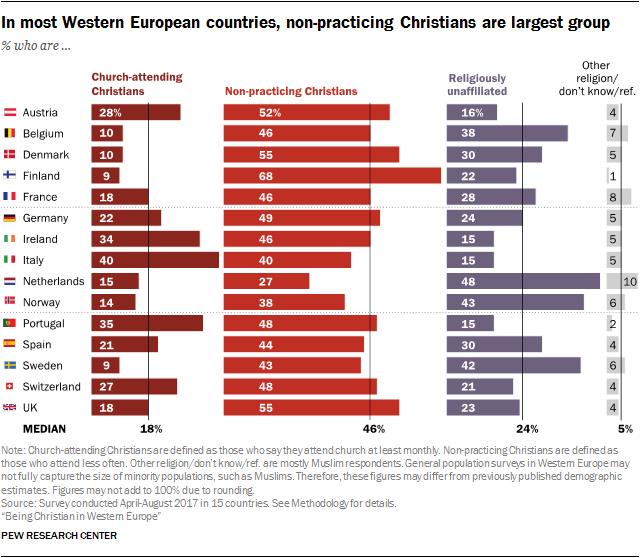

However most adults surveyed still do consider themselves Christians, even if they seldom go to church. Indeed, the survey shows that non-practicing Christians (defined, for the purposes of this report, every bit people who identify as Christians, only attend church services no more than a few times per year) make up the biggest share of the population across the region. In every country except Italy, they are more numerous than church-attention Christians (those who go to religious services at least once a month). In the United Kingdom, for case, there are roughly three times as many non-practicing Christians (55%) as there are church-attention Christians (18%) defined this manner.

Non-practicing Christians as well outnumber the religiously unaffiliated population (people who place as atheist, agnostic or "goose egg in particular," sometimes called the "nones") in most of the countries surveyed.1 And, even afterward a recent surge in clearing from the Center Due east and Due north Africa, at that place are many more non-practicing Christians in Western Europe than people of all other religions combined (Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, etc.).

Non-practicing Christians as well outnumber the religiously unaffiliated population (people who place as atheist, agnostic or "goose egg in particular," sometimes called the "nones") in most of the countries surveyed.1 And, even afterward a recent surge in clearing from the Center Due east and Due north Africa, at that place are many more non-practicing Christians in Western Europe than people of all other religions combined (Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, etc.).

These figures raise some obvious questions: What is the meaning of Christian identity in Western Europe today? And how different are not-practicing Christians from religiously unaffiliated Europeans – many of whom too come from Christian backgrounds?

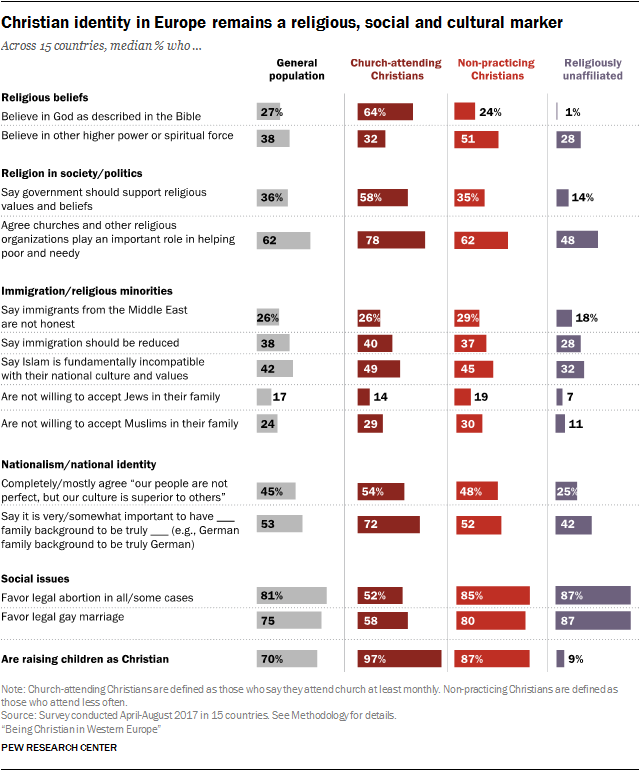

The Pew Research Centre study – which involved more than than 24,000 telephone interviews with randomly selected adults, including near 12,000 non-practicing Christians – finds that Christian identity remains a meaningful mark in Western Europe, even among those who seldom get to church. It is non only a "nominal" identity devoid of applied importance. On the contrary, the religious, political and cultural views of non-practicing Christians often differ from those of church-attending Christians and religiously unaffiliated adults. For example:

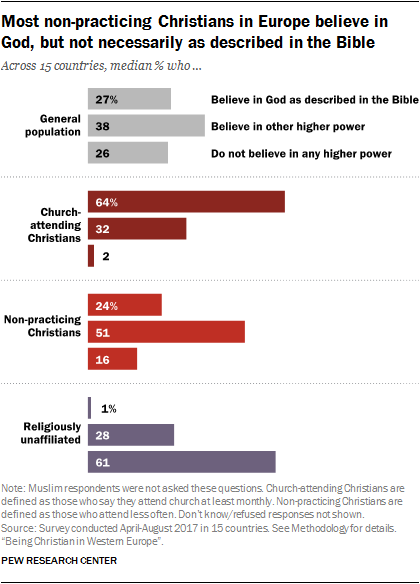

- Although many not-practicing Christians say they do non believe in God "equally described in the Bible," they practice tend to believe in some other college ability or spiritual force. By contrast, most church-attention Christians say they believe in the biblical delineation of God. And a clear majority of religiously unaffiliated adults exercise not believe in whatever type of higher power or spiritual force in the universe.

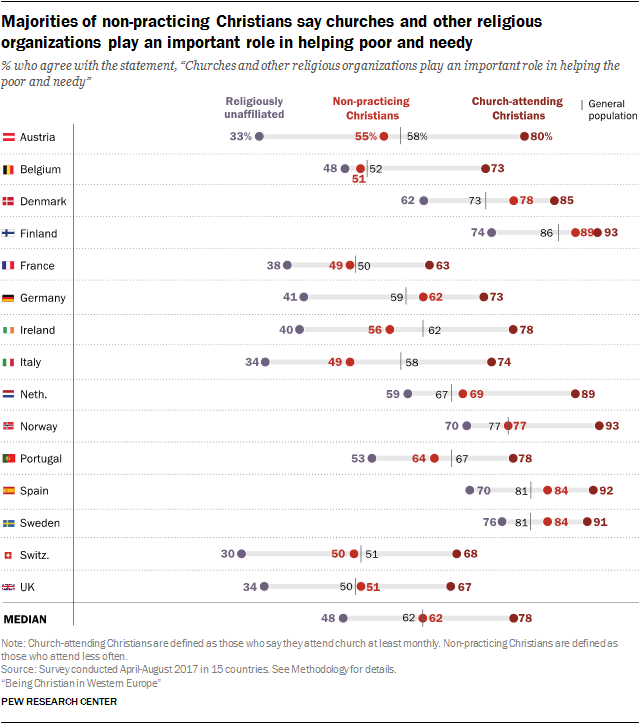

- Non-practicing Christians tend to express more than positive than negative views toward churches and religious organizations, maxim they serve lodge past helping the poor and bringing communities together. Their attitudes toward religious institutions are not quite as favorable as those of church-attention Christians, but they are more likely than religiously unaffiliated Europeans to say churches and other religious organizations contribute positively to society.

- Christian identity in Western Europe is associated with college levels of negative sentiment toward immigrants and religious minorities. On remainder, cocky-identified Christians – whether they attend church or not – are more probable than religiously unaffiliated people to express negative views of immigrants, also as of Muslims and Jews.

- Not-practicing Christians are less likely than church-attention Christians to limited nationalist views. Still, they are more likely than "nones" to say that their civilization is superior to others and that it is necessary to have the country's ancestry to share the national identity (due east.1000., 1 must take Spanish family unit background to be truly Spanish).

- The vast majority of non-practicing Christians, similar the vast majority of the unaffiliated in Western Europe, favor legal abortion and aforementioned-sex marriage. Church-attending Christians are more conservative on these issues, though even among churchgoing Christians, in that location is substantial back up – and in several countries, majority support – for legal abortion and same-sexual activity marriage.

- Near all churchgoing Christians who are parents or guardians of minor children (those under 18) say they are raising those children in the Christian faith. Among non-practicing Christians, somewhat fewer – though still the overwhelming bulk – say they are bringing up their children as Christians. Past contrast, religiously unaffiliated parents generally are raising their children with no religion.

Religious identity and practice are not the merely factors behind Europeans' behavior and opinions on these issues. For instance, highly educated Europeans are generally more accepting of immigrants and religious minorities, and religiously unaffiliated adults tend to accept more years of schooling than non-practicing Christians. But even after statistical techniques are used to command for differences in education, age, gender and political ideology, the survey shows that churchgoing Christians, non-practicing Christians and unaffiliated Europeans express different religious, cultural and social attitudes. (Run across below in this overview and Chapter ane.)

These are amidst the fundamental findings of a new Pew Research Center survey of 24,599 randomly selected adults across 15 countries in Western Europe. Interviews were conducted on mobile and landline telephones from April to August, 2017, in 12 languages. The survey examines not but traditional Christian religious behavior and behaviors, opinions about the office of religious institutions in society, and views on national identity, immigrants and religious minorities, but besides Europeans' attitudes toward Eastern and New Age spiritual ideas and practices. And the 2nd one-half of this Overview more closely examines the beliefs and other characteristics of the religiously unaffiliated population in the region.

While the vast majority of Western Europeans identify equally either Christian or religiously unaffiliated, the survey besides includes interviews with people of other (non-Christian) religions as well as with some who reject to answer questions about their religious identity. But, in near countries, the survey's sample sizes do non permit for a detailed analysis of the attitudes of people in this grouping. Furthermore, this category is composed largely of Muslim respondents, and general population surveys may underrepresent Muslims and other small religious groups in Europe because these minority populations often are distributed differently throughout the country than is the general population; additionally, some members of these groups (especially contempo immigrants) do non speak the national language well enough to participate in a survey. As a result, this report does not try to characterize the views of religious minorities such every bit Muslims, Jews, Buddhists or Hindus in Western Europe.

What is a median?

On many questions throughout this report, median percentages are reported to assist readers see overall patterns. The median is the middle number in a listing of figures sorted in ascending or descending society. In a survey of 15 countries, the median result is the eighth on a list of country-level findings ranked in order.

Non-practicing Christians widely believe in God or another higher power

Most non-practicing Christians in Europe believe in God. Just their concept of God differs considerably from the way that churchgoing Christians tend to conceive of God. While most church-attention Christians say they believe in God "as described in the Bible," not-practicing Christians are more than apt to say that they exercise non believe in the biblical delineation of God, but that they believe in another college power or spiritual force in the universe.

Most non-practicing Christians in Europe believe in God. Just their concept of God differs considerably from the way that churchgoing Christians tend to conceive of God. While most church-attention Christians say they believe in God "as described in the Bible," not-practicing Christians are more than apt to say that they exercise non believe in the biblical delineation of God, but that they believe in another college power or spiritual force in the universe.

For instance, in Catholic-majority Spain, only about one-in-five non-practicing Christians (21%) believe in God "as described in the Bible," while vi-in-ten say they believe in another higher power or spiritual force.

Non-practicing Christians and "nones" also diverge sharply on this question; most unaffiliated people in Western Europe do not believe in God or a higher ability or spiritual force of any kind. (Run into below for more details on belief in God among religiously unaffiliated adults.)

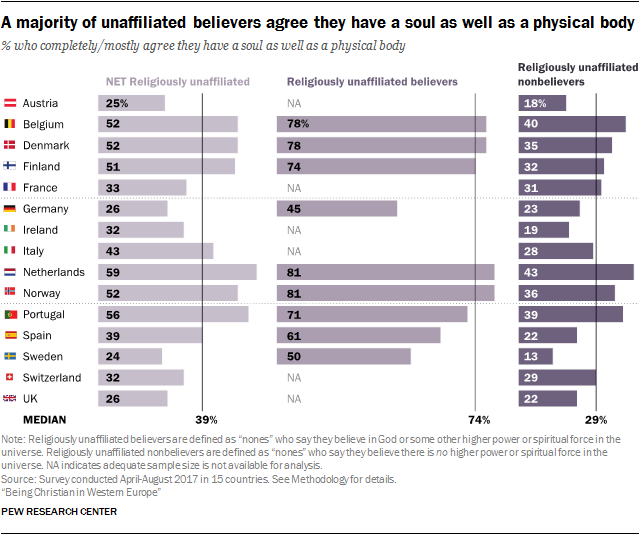

Like patterns – in which Christians tend to hold spiritual behavior while "nones" do non – prevail on a variety of other beliefs, such every bit the possibility of life later decease and the notion that humans have souls apart from their physical bodies. Majorities of non-practicing Christians and church building-attention Christians believe in these ideas. Almost religiously unaffiliated adults, on the other paw, reject conventionalities in an afterlife, and many do not believe they have a soul.

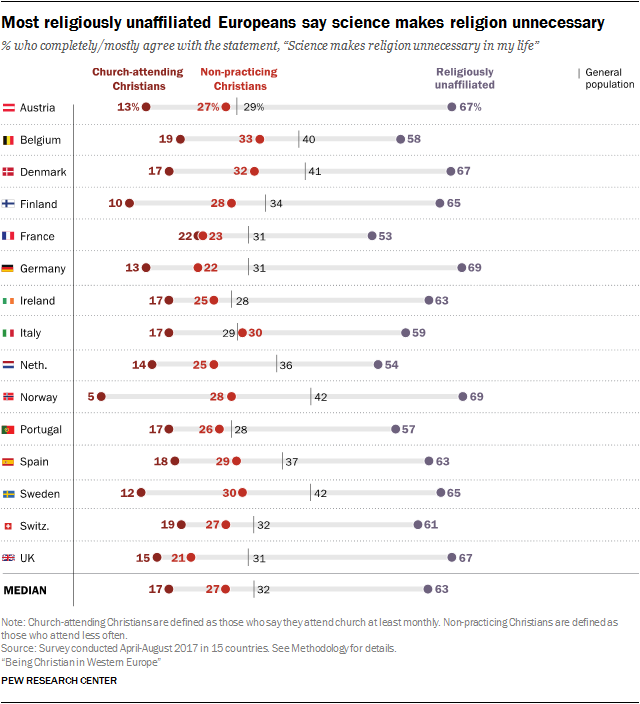

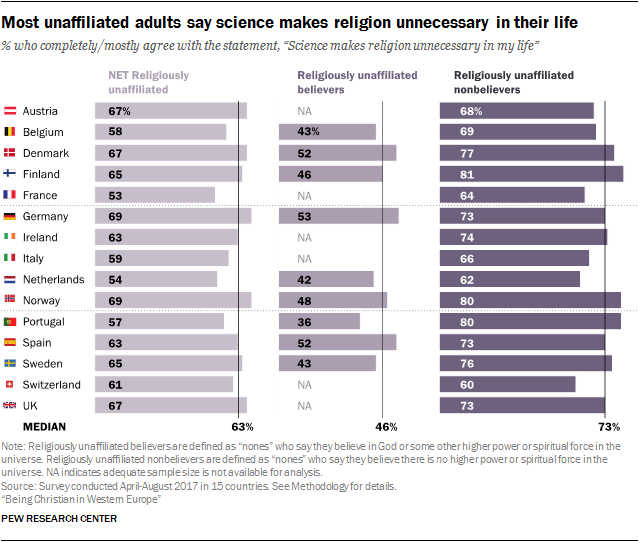

Indeed, many religiously unaffiliated adults eschew spirituality and organized religion entirely. Majorities concur with the statements, "There are no spiritual forces in the universe, but the laws of nature" and "Scientific discipline makes religion unnecessary in my life." These positions are held by smaller shares of church-attending Christians and non-practicing Christians, though in nigh countries roughly a quarter or more of non-practicing Christians say science makes religion unnecessary to them. (For a detailed statistical assay combining multiple questions into scales of religious commitment and spirituality, run into Chapters three and v.)

Views on relationship between government and religion

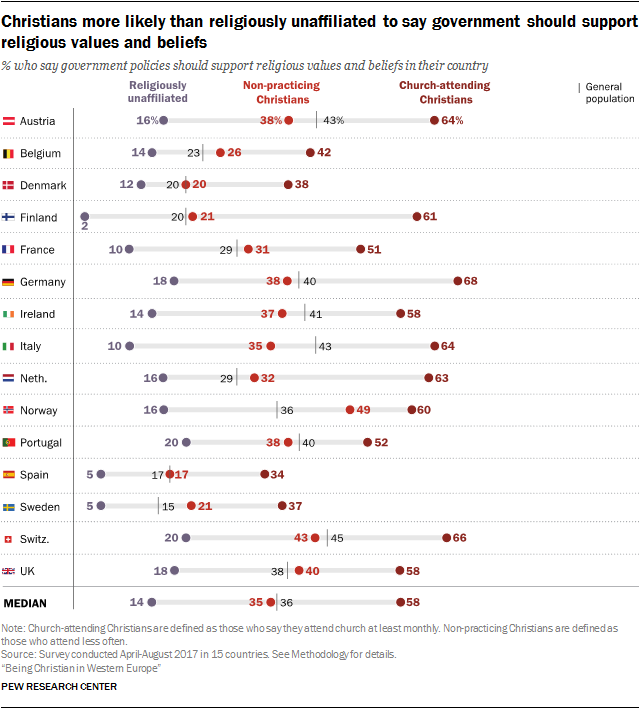

More often than not speaking, Western Europeans do not look favorably on entanglements between their governments and organized religion. Indeed, the predominant view in all fifteen countries surveyed is that religion should be kept separate from government policies (median of 60%), every bit opposed to the position that government policies should support religious values and beliefs in their country (36%).

Non-practicing Christians tend to say religion should be kept out of authorities policy. Still, substantial minorities (median of 35%) of non-practicing Christians remember the authorities should support religious values and beliefs in their state – and they are much more probable than religiously unaffiliated adults to accept this position. For example, in the Great britain, 40% of non-practicing Christians say the government should support religious values and beliefs, compared with 18% of "nones."

In every country surveyed, church-attending Christians are much more than likely than non-practicing Christians to favor government support for religious values. In Republic of austria, for example, a majority (64%) of churchgoing Christians take this position, compared with 38% of not-practicing Christians.

The survey also gauged views on religious institutions, asking whether respondents agree with three positive statements about churches and other religious organizations – that they "protect and strengthen morality in lodge," "bring people together and strengthen community bonds," and "play an important role in helping the poor and needy." Three like questions asked whether they agree with negative assessments of religious institutions – that churches and other religious organizations "are too involved with politics," "focus too much on rules," and "are too concerned with money and power."

Once once more, there are marked differences of opinion on these questions amid Western Europeans beyond categories of religious identity and practise. Throughout the region, not-practicing Christians are more likely than religiously unaffiliated adults to vocalism positive opinions of religious institutions. For case, in Germany, a majority of not-practicing Christians (62%) hold that churches and other religious organizations play an important function in helping the poor and needy, compared with fewer than half (41%) of "nones."

Church building-attending Christians hold especially positive opinions most the role of religious organizations in society. For instance, most three-in-four churchgoing Christians in Belgium (73%), Federal republic of germany (73%) and Italy (74%) concur that churches and other religious institutions play an of import office in helping the poor and needy. (For more assay of results on these questions, meet Chapter 6.)

Both non-practicing and churchgoing Christians are more than likely than the unaffiliated to concord negative views of immigrants, Muslims and Jews

The survey, which was conducted following a surge of immigration to Europe from Muslim-bulk countries, asked many questions about national identity, religious pluralism and immigration.

Most Western Europeans say they are willing to accept Muslims and Jews in their neighborhoods and in their families, and most pass up negative statements about these groups. And, on rest, more than respondents say immigrants are honest and hardworking than say the reverse.

Simply a articulate design emerges: Both church building-attention and not-practicing Christians are more likely than religiously unaffiliated adults in Western Europe to vocalisation anti-immigrant and anti-minority views.

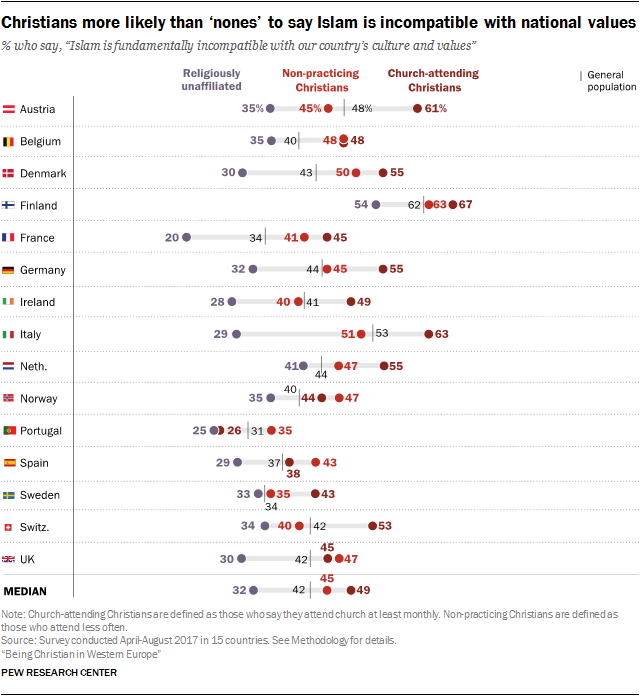

For case, in the UK, 45% of church-attention Christians say Islam is fundamentally incompatible with British values and civilisation, equally do roughly the same share of non-practicing Christians (47%). But among religiously unaffiliated adults, fewer (30%) say Islam is fundamentally incompatible with their country'southward values. In that location is a similar pattern beyond the region on whether there should be restrictions on Muslim women's dress, with Christians more than probable than "nones" to say Muslim women should non be allowed to wear any religious habiliment.

Although current debates on multiculturalism in Europe ofttimes focus on Islam and Muslims, there also are long-standing Jewish communities in many Western European countries. The survey finds Christians at all levels of religious observance are more likely than religiously unaffiliated adults to say they would not be willing to accept Jews in their family, and, on balance, they are somewhat more than likely to concur with highly negative statements about Jews, such equally, "Jews always pursue their own interests, and not the interest of the state they live in." (For farther analysis of these questions, see Chapter i.)

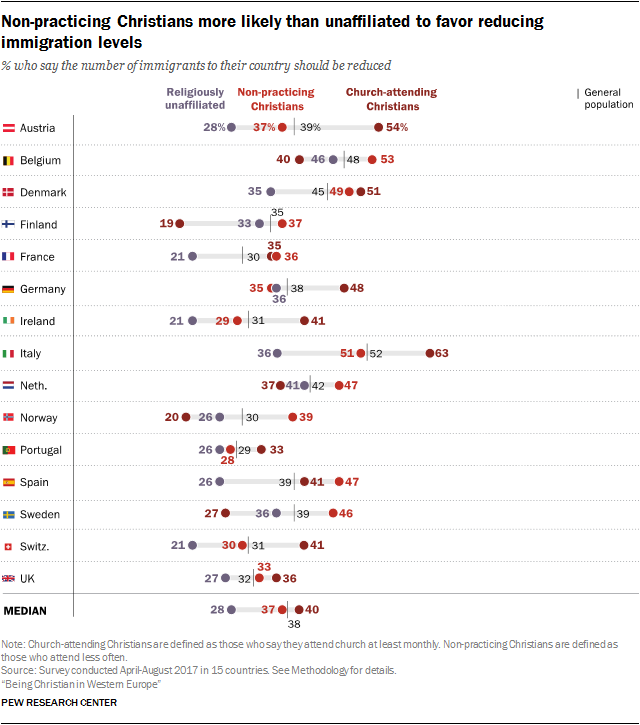

When it comes to clearing, Christians – both churchgoing and non-practicing – are more likely than "nones" in Europe to say immigrants from the Middle Eastward and Africa are not honest or hardworking, and to favor reducing immigration from current levels.2 For example, 35% of churchgoing Christians and 36% of not-practicing Christians in France say immigration to their state should be reduced, compared with 21% of "nones" who take this position.

There are, however, exceptions to this general pattern. In a few places, church building-attending Christians are more accepting of immigration and less likely to say immigration should be reduced. In Finland, for case, just one-in-five churchgoing Christians favor reducing immigration (19%), compared with larger shares amid religiously unaffiliated adults (33%) and not-practicing Christians (37%).

But overall, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish opinions are more than common among Christians, at all levels of practice, than they are among Western Europeans with no religious amalgamation. This is not to say that nigh Christians hold these views: On the reverse, by most measures and in nigh countries surveyed, only minorities of Christians voice negative opinions about immigrants and religious minorities.

In that location also are other factors beyond religious identity that are closely connected with views on clearing and religious minorities. For instance, college education and personally knowing someone who is Muslim tend to go hand in hand with more openness to immigration and religious minorities. And identifying with the political correct is strongly linked to anti-immigration stances.

Still, fifty-fifty after using statistical techniques to control for a wide multifariousness of factors (age, education, gender, political credo, personally knowing a Muslim or a Jewish person, personal assessments of economic well-existence, satisfaction with the country's general management, etc.), Western Europeans who place every bit Christian are more likely than those who have no religious affiliation to limited negative feelings near immigrants and religious minorities.

Are Christian identity and Muslim immigration linked? The broader debate in Europe

Pew Research Center's survey of Western Europe was conducted in the spring and summertime of 2017, following the two highest years of aviary applications on tape. Some scholars and commentators have asserted that the influx of refugees, including many from Muslim-bulk countries, is spurring a revival of Christian identity. Rogers Brubaker, a professor of folklore at UCLA, calls this a reactive Christianity in which highly secular Europeans are looking at new immigrants and saying, in effect: "If 'they' are Muslim, then in some sense 'we' must be Christian."

The survey – a kind of snapshot in time – cannot show that Christian identity is at present growing in Western Europe after decades of secularization. Nor tin can it prove (or disprove) the assertion that if Christian identity is growing, immigration of non-Christians is the reason.

But the survey can help answer the question: What is the nature of Christian identity in Western Europe today, particularly among the large population that identifies every bit Christian but does not regularly get to church? As explained in greater detail throughout this study, the findings suggest that the answer is partly a matter of religious beliefs, partly a matter of attitudes toward the function of religion in society, and partly a thing of views on national identity, immigrants and religious minorities.

This confluence of factors may not surprise close observers of European politics. Olivier Roy, a French political scientist who studies both Islam and secularization, writes that, "If the Christian identity of Europe has become an outcome, it is precisely considering Christianity as faith and practices faded away in favor of a cultural marker which is more and more turning into a neo-ethnic marker ('true' Europeans versus 'migrants')."

Some commentators have expressed stiff misgivings nearly the promotion of "cultural" Christian identity in Europe, seeing it equally driven largely past fear and misunderstanding. In the "present context of high levels of fright of and hostility to Muslims," writes Tariq Modood, professor of sociology, politics and public policy at the University of Bristol in the UK, efforts to develop cultural Christianity every bit an "ideology to oppose Islam" are both a claiming to pluralism and equality, and "a risk to commonwealth."

Others see a potential revival of Christianity in Western Europe equally a bulwark confronting extremism. While calling himself an "incurable atheist," the British historian Niall Ferguson said in a 2006 interview that "organised Christianity, both in terms of observance and in terms of faith, sail[ed] off a cliff in Europe sometime in the 1970s, 1980s," leaving European societies without "religious resistance" to radical ideas. "In a secular order where nobody believes in anything terribly much except the next shopping spree, it's really quite easy to recruit people to radical, monotheistic positions," Ferguson said.

But not everyone agrees on clearing's bear on. British writer and lecturer Ronan McCrea contends that Muslim migration is making Europe more secular, not less. "Previously, many of those who are not especially religious were content to draw themselves as Christian on cultural grounds," he writes. "But as religion and national identity accept gradually begun to divide, religious identity becomes more than a question of ideology and belief than membership of a national community. This has encouraged those who are not true believers to move from a nominal Christian identity to a more than clearly non-religious one."

In Western Europe, religion strongly associated with nationalist sentiment

Overall levels of nationalism vary considerably beyond the region.3 For example, solid majorities in some countries (such as Italia and Portugal) and fewer than half in others (such as Sweden and Kingdom of denmark) say that information technology is of import to take ancestors from their land to truly share the national identity (e.g., to accept Danish ancestry to exist truly Danish).

Within countries, non-practicing Christians are less probable than churchgoing Christians to say that ancestry is key to national identity. And religiously unaffiliated people are less probable than both churchgoing and non-practicing Christians to say this.

For instance, in France, near three-quarters of church-attention Christians (72%) say information technology is of import to have French ancestry to exist "truly French." Among not-practicing Christians, 52% have this position, simply this is still higher than the 43% of religiously unaffiliated French adults who say having French family background is important in guild to be truly French.

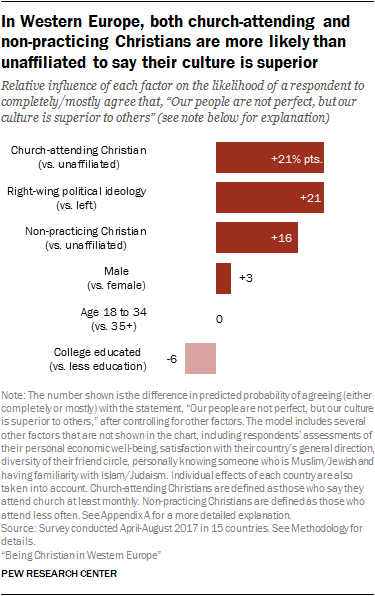

Both non-practicing and churchgoing Christians are more likely than "nones" to agree with the statement, "Our people are not perfect, merely our culture is superior to others." And boosted statistical assay shows that this holds true fifty-fifty after decision-making for historic period, gender, education, political credo and other factors.

In other words, Christians as a whole in Western Europe tend to express higher levels of nationalist sentiment. This overall design is not driven by nationalist feelings solely amid highly religious Christians or solely among non-practicing Christians. Rather, at all levels of religious observance, these views are more common among Christians than among religiously unaffiliated people in Europe.

In other words, Christians as a whole in Western Europe tend to express higher levels of nationalist sentiment. This overall design is not driven by nationalist feelings solely amid highly religious Christians or solely among non-practicing Christians. Rather, at all levels of religious observance, these views are more common among Christians than among religiously unaffiliated people in Europe.

Birthday, the survey asked more than 20 questions about possible elements of nationalism, feelings of cultural superiority, attitudes toward Jews and Muslims, views on immigrants from various regions of the world, and overall levels of immigration. Many of these views are highly correlated with each other. (For example, people who limited negative attitudes toward Muslims and Jews are also more likely to express negative attitudes toward immigrants, and vice versa.) As a upshot, researchers were able to combine 22 individual questions into a scale measuring the prevalence of nationalist, anti-immigrant and anti-minority sentiments in each country and to behave boosted statistical analysis of the factors associated with these sentiments in Western Europe today. For details of this analysis, see Chapter one.

Same-sex marriage, abortion widely accepted by non-practicing Christians

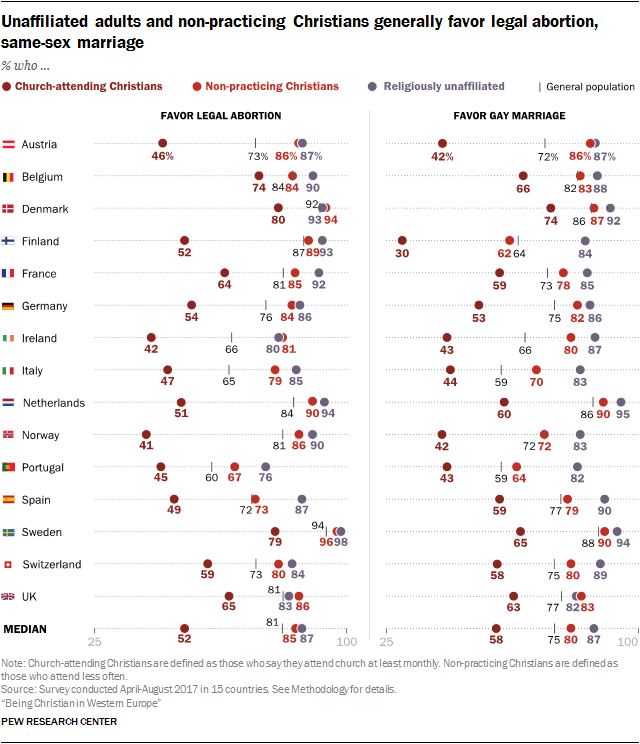

Vast majorities of not-practicing Christians and religiously unaffiliated adults across Western Europe favor legal abortion and same-sex marriage. In some countries, there is not much divergence on these questions between the attitudes of Christians who rarely nourish church and adults who exercise not chapter with whatever religion.

In every state surveyed, on the other hand, church-attending Christians are considerably more than conservative than both non-practicing Christians and religiously unaffiliated adults on questions well-nigh ballgame and aforementioned-sex marriage.

Instruction has a strong influence on attitudes on both issues: Higher-educated respondents are considerably more likely than those with less education to favor legal abortion and same-sexual activity wedlock. On balance, women are more likely than men to favor legal gay marriage, merely their attitudes are largely similar on abortion.

Summing up: On what issues do not-practicing Christians resemble 'nones'? And on what measures are they similar to church building-attention Christians?

While the religious, political and cultural views of not-practicing Christians in Western Europe are oftentimes distinct from those of church-attending Christians and religiously unaffiliated adults ("nones"), on some bug non-practicing Christians resemble churchgoing Christians, and on others they largely align with "nones."

Religious beliefs and attitudes toward religious institutions are ii areas of broad similarity between non-practicing Christians and church-attending Christians. Well-nigh non-practicing Christians say they believe in God or some higher ability, and many think that churches and other religious organizations make positive contributions to society. In these respects, their perspective is similar to that of churchgoing Christians.

On the other mitt, abortion, gay marriage and the role of faith in government are iii areas where the attitudes of not-practicing Christians broadly resemble those of religiously unaffiliated people ("nones"). Solid majorities of both not-practicing Christians and "nones" say they remember that abortion should be legal in all or most cases and that gays and lesbians should be allowed to marry legally. In improver, most non-practicing Christians, along with the vast majority of "nones," say faith should be kept out of government policies.

When asked whether it is important to have been born in their state, or to have family background there, to truly share the national identity (eastward.g., important to accept Spanish beginnings to be truly Spanish), non-practicing Christians mostly are somewhere in betwixt the religiously unaffiliated population and church building-attending Christians, who are most inclined to link birthplace and ancestry with national identity.

Many in all 3 groups refuse negative statements almost immigrants and religious minorities. Simply non-practicing Christians and church-attending Christians are generally more than likely than "nones" to favor lower levels of immigration, to express negative views toward immigrants from the Center Eastward and sub-Saharan Africa, and to agree with negative statements about Muslims and Jews such as, "In their hearts, Muslims want to impose their religious police force on everyone else" in their country or "Jews ever pursue their own interests and not the interest of the state they live in."(For further analysis of these questions, run into Chapter 1.)

Overall, the study shows a strong clan between Christian identity and nationalist attitudes, every bit well every bit views of religious minorities and immigration, and a weaker clan betwixt religious delivery and these views. This finding holds regardless of whether religious commitment among Christians is measured through church attendance alone, or using a calibration that combines omnipresence with 3 other measures: belief in God, frequency of prayer and importance of religion in a person's life. (See Chapter 3 for a detailed analysis of the scale of religious commitment.)

Religious observance and attitudes toward minorities among Catholics and Protestants in Western Europe

Although people in some predominantly Catholic countries in Europe, including Portugal and Italia, are more religiously observant than others in the region, Catholics and Protestants overall in Western Europe brandish similar overall levels of observance.

Although people in some predominantly Catholic countries in Europe, including Portugal and Italia, are more religiously observant than others in the region, Catholics and Protestants overall in Western Europe brandish similar overall levels of observance.

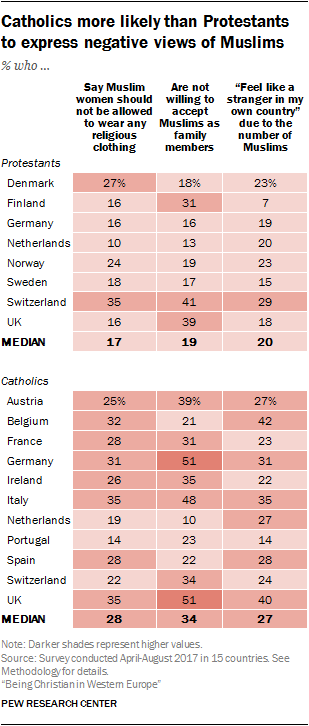

But Catholics and Protestants in the region differ in their attitudes toward religious minorities. For example, Catholics are more likely than Protestants to hold negative views of Muslims: Catholics are more likely than Protestants to say they would non be willing to have Muslims as family unit members, that Muslim women in their country should non be allowed to clothing any religious vesture, and that they agree with the statement, "Due to the number of Muslims here, I feel similar a stranger in my own country."

Differences between Catholics and Protestants on these issues can be difficult to disentangle from historical and geographic patterns in Western Europe, where Catholic-majority countries are primarily concentrated in the southward, while the north is more heavily Protestant. But in a handful of countries with substantial populations of both Catholics and Protestants – including the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and Germany – more Catholics than Protestants hold negative attitudes toward Muslims. For example, in the United kingdom, 35% of Catholics and sixteen% of Protestants say Muslim women in their country should not be immune to wear any religious wearable. In Switzerland, all the same, the opposite is truthful; 35% of Swiss Protestants express this view, compared with 22% of Catholics.

Context of the survey

The survey was conducted in mid-2017, afterwards immigration emerged as a front-and-heart issue in national elections in several Western European countries and as populist, anti-immigration parties questioned the identify of Muslims and other religious and ethnic minorities in Federal republic of germany, French republic, the Britain and elsewhere.

Muslims at present make up an estimated 4.9% of the population of the European Matrimony (plus Norway and Switzerland) and somewhat higher shares in some of Western Europe'due south nigh populous countries, such as French republic (an estimated 8.8%), the UK (6.iii%) and Germany (6.1%). These figures are projected to continue to increase in coming decades, even if there is no more than immigration to Europe.

The survey asked not only virtually attitudes toward Muslims and Jews, but also nearly Catholics' and Protestants' views of i another. The findings about Protestant-Catholic relations were previously released before the commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation in Federal republic of germany.4

This report besides includes material from twenty focus groups convened past Pew Research Eye in the months following the survey's completion in five of the countries surveyed. The focus groups in France, Germany, Kingdom of spain, Sweden and the Great britain provided an opportunity for participants to discuss their feelings about pluralism, immigration, secularism and other topics in more than particular than survey respondents typically can give when responding to a questionnaire. Some conclusions from focus groups are included in illustrative sidebars throughout the report.

This study, funded past The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, is office of a larger effort past Pew Inquiry Center to empathize religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The Center previously has conducted organized religion-focused surveys across sub-Saharan Africa; the Eye E-N Africa region and many other countries with large Muslim populations; Latin America; State of israel; Fundamental and Eastern Europe; and the Us.

The rest of this Overview examines what it ways to be a "none" in Western Europe, including the extent of religious switching from Christianity to the ranks of the religiously unaffiliated and the reasons "nones" give for leaving their childhood faith. It also looks at their beliefs about religion and spirituality, including a closer look at the attitudes of religiously unaffiliated adults who say they do believe there is a God or some other higher power or spiritual force in the universe.

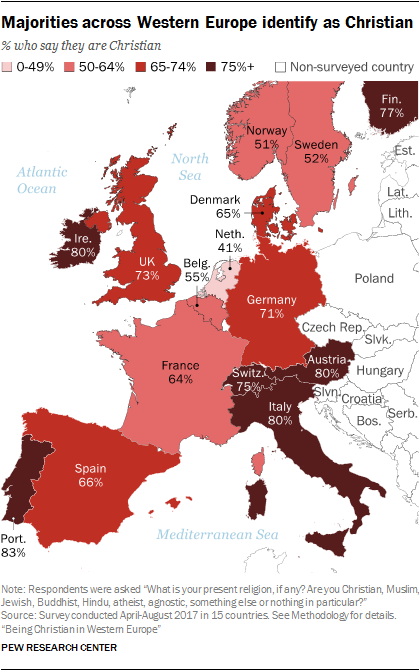

Europe's changing religious mural: Declines for Christians, gains for unaffiliated

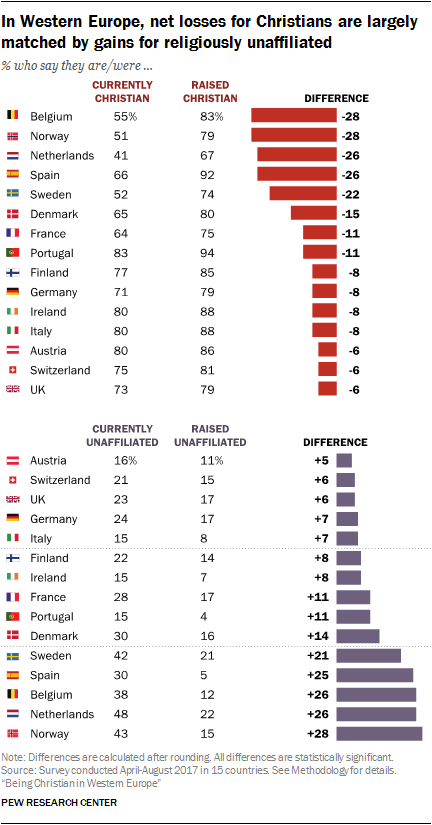

Most people in Western Europe draw themselves every bit Christians. But the percent of Christians appears to have declined, especially in some countries. And the internet losses for Christianity have been accompanied past net growth in the numbers of religiously unaffiliated people.

Most people in Western Europe draw themselves every bit Christians. But the percent of Christians appears to have declined, especially in some countries. And the internet losses for Christianity have been accompanied past net growth in the numbers of religiously unaffiliated people.

Beyond the region, fewer people say they are Christian now than say they were raised every bit Christians. The opposite is true of religiously unaffiliated adults – many more people currently are religiously unaffiliated than the share who were raised with no organized religion (i.e., as atheist, agnostic or "null in particular"). For case, 5% of adults in Espana say they were raised with no religion, while 30% now fit this category, a difference of 25 percentage points. The religiously unaffiliated have seen similarly big gains in Belgium, the netherlands, Norway and Sweden.

Sidebar: Religious identity in Western Europe over time

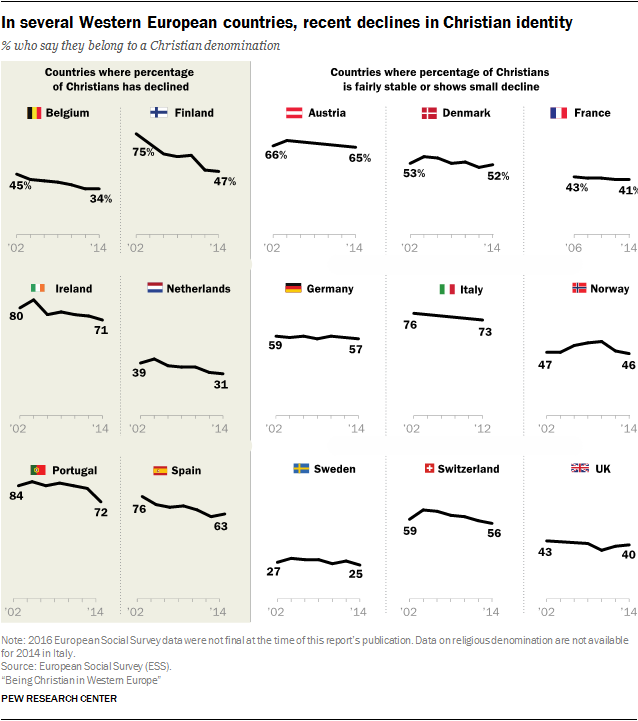

Several countries in Western Europe have been collecting census information on religion for decades, and these data (from Austria, Finland, Republic of ireland, kingdom of the netherlands, Portugal and Switzerland) point that the percentage of the population that identifies as Christian has fallen substantially since the 1960s, while the share of the population that does not place with any religion has risen.5

More contempo data collected past the European Social Survey (ESS) since 2002 show a continuation of the long-term tendency in some countries. Christianity has experienced relatively rapid declines in Kingdom of belgium, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, Portugal and Kingdom of spain. But in the ix other countries included in the Pew Research Heart survey, the ESS finds the share of Christians has either been relatively stable or has declined only modestly, suggesting that the rate of secularization varies considerably from country to state and may have slowed or leveled off in some places in contempo years.

Due to major differences in question wording, the ESS estimates of the percentage of Christians in each country differ considerably from Pew Research Center estimates. The ESS asks what is known equally a "2-step" question about religious identity: Respondents first are asked, "Exercise you consider yourself as belonging to any particular religion or denomination?" People who say "Yep" are and so asked, "Which one? Roman Catholic, Protestant, Eastern Orthodox, other Christian denomination, Jewish, Islamic, Eastern religions or other not-Christian religions." Pew Enquiry Eye surveys ask a "one-step" question, "What is your nowadays faith, if whatever? Are y'all Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, doubter, something else or zippo in particular?"

Using the ESS question diction and two-footstep approach consistently yields lower shares of religiously affiliated respondents (including Christians) in Western Europe. For example, in the Netherlands, 31% of respondents identify with a Christian denomination in the 2022 ESS, while in the Pew Research Center survey, 41% identify as Christian. Presumably, this is considering some respondents who are relatively low in religious practice or belief would reply the kickoff question posed past ESS by saying they have no religion, while the same respondents would identify equally Christian, Muslim, Jewish, etc., if presented with a list of religions and asked to choose amongst them. The impact of these differences in question wording and format may vary considerably from country to land.

Who are Western Europe's religiously unaffiliated?

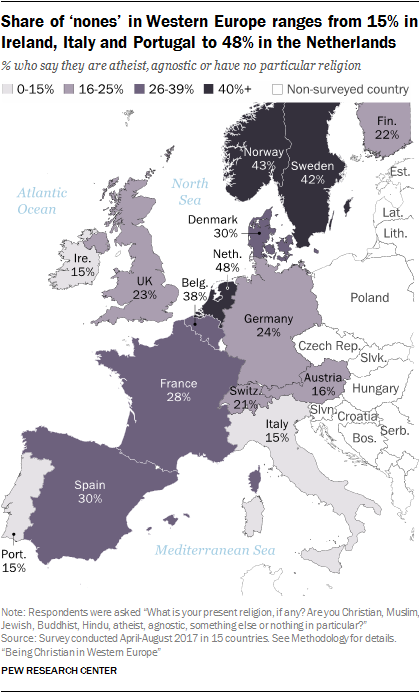

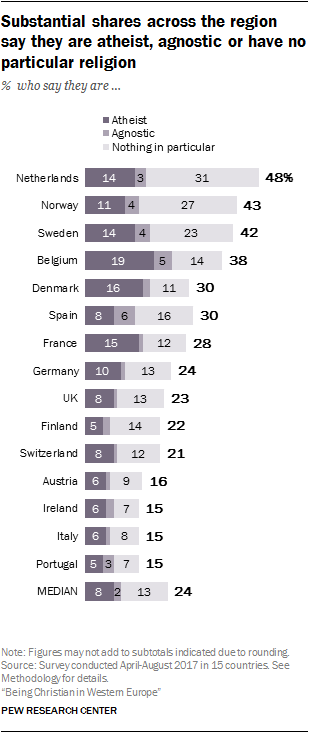

While Christians (taken as a whole) are by far the largest religious grouping in Western Europe, a substantial minority of the population in every country is religiously unaffiliated – too sometimes called "nones," a category that includes people who identify as atheist, agnostic or "nothing in particular." The unaffiliated portion of the adult population ranges from as high every bit 48% in the Netherlands to 15% in Ireland, Italy and Portugal.

Demographically, "nones" in Western Europe are relatively young and highly educated, as well equally disproportionately male.

Demographically, "nones" in Western Europe are relatively young and highly educated, as well equally disproportionately male.

Within the unaffiliated category, those who depict their religious identity as "nothing in particular" make up the biggest group (relative to atheists and agnostics) in well-nigh countries. For case, fully three-in-ten Dutch adults (31%) depict their religious identity in this way, compared with fourteen% who are cocky-described atheists and 3% who consider themselves agnostics.

But in some other places, such as Belgium, Denmark and France, atheists are at least every bit numerous as those in the "nothing in item" category. Agnostics, past comparison, have a smaller presence throughout Western Europe.

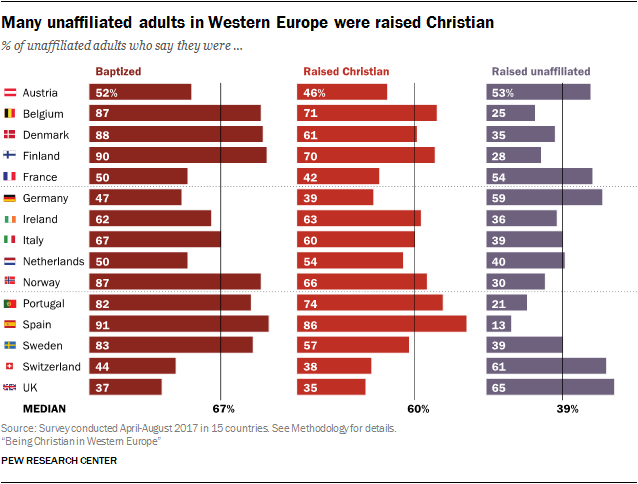

A bulk of "nones" in nearly countries surveyed say they were baptized, and many of them besides say they were raised as Christians. Overall, more religiously unaffiliated adults in Europe say they were raised Christian (median of 60%) than say they were raised with no religious amalgamation (median of 39%).

However, these figures vary widely from country to land. For case, the vast majority of unaffiliated adults in Spain (86%) and Portugal (74%) say they were raised as Christians. In the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, by contrast, roughly two-thirds (65%) of adults who currently take no religious affiliation say they were raised that way.

What has led Europeans to shed their religious identity?

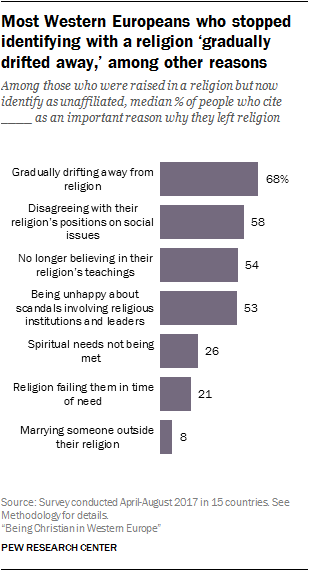

For religiously unaffiliated adults who were raised equally Christians (or in some other organized religion), the survey posed a series of questions asking near potential reasons they left religion behind.six Respondents could select multiple reasons every bit important factors why they stopped identifying with their babyhood organized religion.

For religiously unaffiliated adults who were raised equally Christians (or in some other organized religion), the survey posed a series of questions asking near potential reasons they left religion behind.six Respondents could select multiple reasons every bit important factors why they stopped identifying with their babyhood organized religion.

In every state surveyed, most "nones" who were raised in a religious grouping say they "gradually drifted away from faith," suggesting that no 1 particular effect or single specific reason prompted this change.7 Many also say that they disagreed with church positions on social issues like homosexuality and abortion, or that they stopped believing in religious teachings. Majorities in several countries, such as Kingdom of spain (74%) and Italian republic (60%), likewise cite "scandals involving religious institutions and leaders" equally an important reason they stopped identifying equally Christian (or with another religious group).

Smaller numbers requite other reasons, such as that their spiritual needs were not existence met, their childhood faith failed them when they were in need, or they married someone exterior their religious group.

For more item on patterns of religious switching in Western Europe and the reasons people give for their choices, see Chapter 2.

Religiously unaffiliated Europeans tend to express different attitudes toward Muslims depending on how they were raised

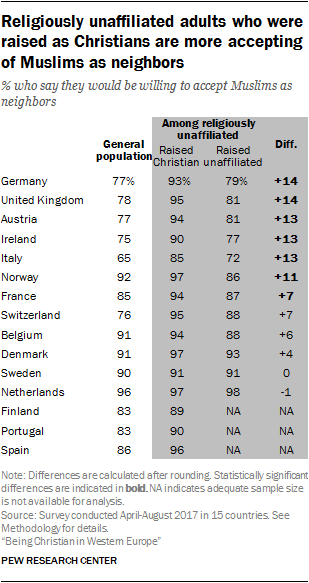

People who have left Christianity in favor of no religious identity may have multiple reasons for doing so. But their attitudes, overall, are more than positive toward religious minorities than are the views of either Christians overall or "nones" who say they were raised with no religious identity.

People who have left Christianity in favor of no religious identity may have multiple reasons for doing so. But their attitudes, overall, are more than positive toward religious minorities than are the views of either Christians overall or "nones" who say they were raised with no religious identity.

On balance, those who were raised Christian and are now religiously unaffiliated are less likely than those who were ever unaffiliated to say Islam is fundamentally incompatible with their national culture and values, or to take the position that Muslim women in their country should not be allowed to wear religious clothing.

They also are more likely to limited acceptance of Muslims. For case, in several countries, higher shares of "nones" who were raised Christian than those who were raised unaffiliated say they would be willing to accept Muslims as neighbors.

Definitive reasons for this pattern are beyond the scope of the data in this study. But it is possible that some Western Europeans may have given up their religious identity, at least in role, because it was associated with more conservative views on a multifariousness of issues, such as multiculturalism, sexual norms and gender roles. It also may be that their attitudes toward immigrants shifted along with the change in their religious identity. Or, information technology could be that another, unknown cistron (political, economical, demographic, etc.) underlies both their switching from Christian to unaffiliated and their views of immigrants and religious minorities.

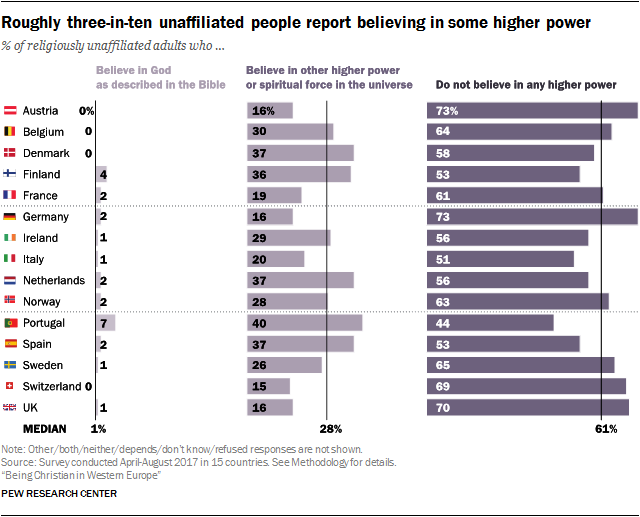

Most unaffiliated Europeans do not believe in a higher power, just a substantial minority concur some spiritual beliefs

Regardless of how they were raised, "nones" across Western Europe seldom partake in traditional religious practices. Few, if any, religiously unaffiliated adults say they attend religious services at least monthly, pray daily, or say faith is "very" or even "somewhat" of import in their lives.

Most "nones" in Western Europe besides affirm they are truly nonbelievers: Not just do majorities in all countries surveyed say they do not believe in God, but nigh besides clarify (in a follow-up question) that they practice not believe in any higher power or spiritual force.

Still, substantial shares of "nones" in all 15 countries surveyed, ranging from 15% in Switzerland to 47% in Portugal, limited belief in God or some other spiritual force in the universe. Even though few – if whatever – of these religiously unaffiliated believers say they attend church building monthly or pray daily, they express attitudes toward spirituality that are different from those of most other "nones."

For example, religiously unaffiliated believers – the subset of "nones" who say they believe in God or some other higher power or spiritual force – are particularly likely to believe they have a soul as well as a physical body, including roughly viii-in-10 in the Netherlands and Kingdom of norway. Amidst the larger group of "nones" who practice not believe in any higher power, conventionalities in a soul is much less common.

The survey as well posed questions virtually the concepts of fate and reincarnation, and near astrology, fortune tellers, meditation, yoga (every bit a spiritual practice, not merely as exercise), the "evil middle" and belief in "spiritual free energy located in physical things, such as mountains, trees or crystals." Nearly Western European "nones" exercise non concord or engage in these beliefs and practices, which are often associated with Eastern, New Age or folk religions. But religiously unaffiliated respondents who believe in a higher power or spiritual force are more than likely than those who do non to concord these beliefs.

While many "nones" in Europe express skeptical or negative views most the value of religion, religiously unaffiliated believers are considerably less likely than nonbelievers to concord anti-religious attitudes. For example, in Belgium, 43% of assertive "nones" agree that science makes faith unnecessary, compared with 69% of unaffiliated nonbelievers. And in Germany, 35% of unaffiliated believers say that religion causes more than harm than good, compared with 55% of nonbelieving "nones."

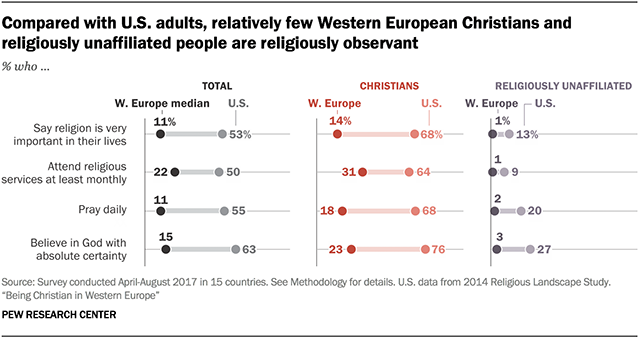

Western Europeans are less religious than Americans

The vast bulk of adults in the U.s.a., similar the bulk of Western Europeans, continue to place as Christian (71%). But on both sides of the Atlantic, growing numbers of people say they are religiously unaffiliated (i.e., atheist, agnostic or "nothing in particular"). Nigh a quarter of Americans (23%, every bit of 2014) fit this description, comparable to the shares of "nones" in the UK (23%) and Germany (24%).

However Americans, overall, are considerably more religious than Western Europeans. Half of Americans (53%) say religion is "very important" in their lives, compared with a median of just 11% of adults beyond Western Europe. Among Christians, the gap is fifty-fifty bigger – two-thirds of U.S. Christians (68%) say religion is very of import to them, compared with a median of 14% of Christians in the 15 countries surveyed across Western Europe. Only even American "nones" are more than religious than their European counterparts. While ane-in-eight unaffiliated U.S. adults (13%) say faith is very important in their lives, hardly whatsoever Western European "nones" (median of one%) share that sentiment.

Similar patterns are seen on belief in God, attendance at religious services and prayer. In fact, past some of these standard measures of religious commitment, American "nones" are as religious as — or fifty-fifty more religious than — Christians in several European countries, including France, Federal republic of germany and the Uk.

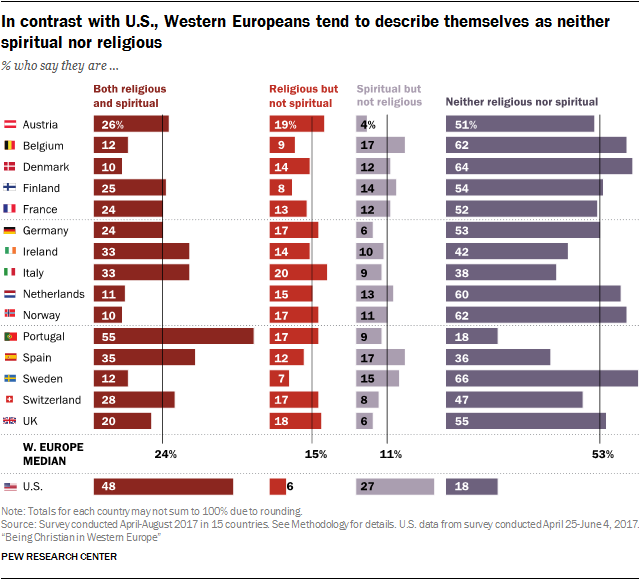

Additionally, the survey asked respondents whether they consider themselves religious and, separately, whether they consider themselves spiritual. These ii questions, combined, result in four categories: those who describe themselves every bit both religious and spiritual, spiritual but non religious, religious but not spiritual, and neither religious nor spiritual.

The largest group across Western Europe (a median of 53%) is "neither religious nor spiritual." In most every land surveyed, roughly four-in-10 or more adults, including majorities in several countries, say they are neither religious nor spiritual. The biggest exception is Portugal, where more than half of adults (55%) say they are both religious and spiritual.

Smaller shares of populations in nearly countries say they are spiritual simply not religious, or religious but not spiritual.

The religious makeup of Western Europe by this measure is significantly dissimilar from that of the United States. The largest group in the U.Due south. is both religious and spiritual (48%), compared with a median of 24% across Western Europe. Americans are as well considerably more probable than Western Europeans to say they think of themselves as spiritual but non religious; 27% of Americans say this, compared with a median of 11% of Western Europeans surveyed.

Very few religiously unaffiliated adults – 2% to four% in nearly every Western European country surveyed – say they consider themselves to be religious people. While somewhat larger shares (median of nineteen%) consider themselves spiritual, this is still much lower than in the United States, where most half of "nones" depict themselves every bit spiritual (including 45% who say they are spiritual just non religious).

A previously published analysis of data from xv European countries used an older version of survey weights. Since and then, Pew Research Center has improved the survey weights for greater accurateness leading to slight differences in some numbers betwixt the two publications. The substantive findings of the previous publication are not affected by the revised weights. Please contact the Center for questions regarding weighting adjustments.

silbermanbreas1983.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/05/29/being-christian-in-western-europe/

0 Response to "Born again Christains Are Likely to Hold Conservative Views"

Post a Comment